Everyone who reads the Bible comes across passages that make them deeply uncomfortable and raise questions about who God is, what he values, and how his people behave. I recall my 5-year-old son asking me what rape was after reading his new “grown up Bible” and arriving at Genesis 34. Let alone my own feelings of horror upon reading Judges 19. When you take the accounts of the mistreatment of women in the Bible, and add to them the growing societal view that God is a misogynist, that Christians are patriarchally overbearing, and that the Bible regards women as second-class citizens responsible for the fall, it’s no wonder that we start to ask questions: Is God sexist? Does he value women?

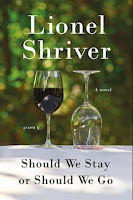

Karen Soole’s refreshing offering,

Liberated, seeks to “address the fear that God does not exalt or dignify women” (p. 13). She takes readers from Genesis to Revelation, encouraging them to ask “does God offer me liberation or oppression? Can I trust that God is good?” (p. 14). The bulk of attention is given to the Old Testament, acknowledging it “stands accused of being a book that has been used to establish male power and confine women” (p. 22). She does not “directly address the differences in church practice concerning women’s ministry” (p. 13), noting that this has been done extensively elsewhere.

Over the course of twelve chapters, Soole honestly and sensitively addresses the concerns raised by the presentation and treatment of women in the Bible. She explores both current and historical cultural climates, naming errors in both, for “could it be that that it is the traditions of men, not the Word of God, that is the heart of the problem?” (p. 22). She then turns to show how these concerns are met by the gospel. Each chapter brings the reader to Jesus and what he has done, for women and men alike. So, while this is indeed an informative and well researched work, it is also winsomely apologetic and evangelistic. Each chapter also finishes with questions for further thought or conversation and a small Bible study.

Beginning with creation, we see that “men and women are equally created by God, equal in dignity, and equal in worth” with a “beautiful interdependence and mutuality” (p. 30). Genesis 2 “is not pointing to the imperfection of woman; rather, it reveals the incompleteness of man, he was the one lacking” (p. 37). Exploring the fall, and the accusation that Eve was somehow more sinful than Adam, Soole observes, “Adam and Eve share responsibility, but their sin is defined differently: Eve was deceived, and Adam was disobedient. Both are guilty” (p. 47).

Continuing through the Old Testament, Soole explores the fallout of sin in relationships (e.g., Tamar and Judah) and then arrives at Judges 19, an account of such evil that no one can be unaffected by it:

Why does the Bible describe such ugliness? Not because God approves of it.… It isn’t there to show us how to live but how we do live. It is here because God doesn’t hide from us the depths of savagery we are capable of. We may want to close our eyes and ears to this woman’s cries, but God wants us to see and understand. What happened to this woman is a reflection of what has happened to other young women. (p. 92)

These hard passages are dealt with sensitively and openly. I appreciated Soole’s willingness to deal with almost every uncomfortable presentation of women in the Bible. At points I wondered if these chapters moved a little too quickly past the issues they raised and to the gospel message. Sometimes we need to dwell in God’s compassion and mercy and meditate on how he stands by us in our pain and our distress. Suggestions for how to manage these passages with pastoral sensitivity may also have been helpful, although she models this implicitly.

Chapter 8 (“Worrying Laws”) addresses the Old Testament teaching concerning polygamy, rape, trials, and purification. Soole presents an interesting interpretation of Numbers 5 (the test for an unfaithful wife), suggesting that it is entirely determined by a supernatural answer, rather than being a trial by ordeal. She also suggests that the purification laws of Leviticus 12:1–8, which decree fourteen days of uncleanness after delivering a daughter (compared to seven for a son), could be for physiological reasons, to avoid the temptation of cult fertility practices, and to protect a woman from the retrying for a son too soon after delivery (p. 120). Not all passages that describe intriguing ways of treating women were addressed (e.g., Lev 27:1–9, Num 30–31), but the general principles were mostly covered.

Regarding education and wisdom, she draws on the wise woman of Proverbs 31 and Abigail’s interactions with David (1 Sam 25), noting that God values women with integrity, skills and wisdom, which can be used for good inside and outside the home. By way of application, she argues,

There is considerable freedom for women to engage in intellectual pursuits, choose challenging careers, or work at home or in their communities. But their minds should stir beyond the domestic sphere, and their eyes should be raised far beyond career opportunities. God’s Word encourages women to lift their thoughts to even higher things and to seek true wisdom. (p. 139)

Soole reflects on how the Bible uses the image of an adulterous wife to demonstrate Israel’s rebellion against God. It is a graphic illustration that “is there to help us grasp the impact of our rejection of God and to feel the weight of our indifference and dismissal of God” (pp. 153–54). Finally, she turns to marriage, noting that “some Christians give the impression that marriage is the ultimate goal in life” (p. 157). She honors both singleness and marriage, and rightly laments that a distortion of submission has resulted in the abuse of some women. Instead, “God’s design for marriage is not one of control and ownership but a relationship for the mutual good of the other” (p. 168).

While there is no chapter on Jesus’s interactions with women, many of these are woven throughout as a way of bringing the reader to the gospel (e.g., the woman at the well). There may have been value in drawing these together more explicitly, and including some other passages (e.g., the woman anointing Jesus with perfume, and the Syrophoenician woman).

Her conclusion, straight from God’s heart and written in his word, is that women (and men) are valuable and created in God’s image. God cares for them and loves to protect them, even though there are times when the world’s evil is all too prominent. Yes, all are sinful and fall short. Yet Jesus came to save women (and men), offering them new life—honoured, respected, loved, and redeemed.

While many who are drawn to read

Liberated will likely be women, it is a book written for everyone and relevant for all, whether new Christians, those exploring who God is, those established in churches, or those in church leadership.